Ostrich Eggshell Beads Reveal 10,000 Years of Cultural Interaction Across Africa

New archeological analysis challenges long-standing hypotheses about ostrich eggshell beads and the spread of pastoralism in Africa.

In a new study published in PLOS ONE, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History’s Department of Archaeology present an expanded analysis of African ostrich eggshell beads, testing the hypothesis that larger beads signal the arrival of herders. The data reveals a more nuanced interpretation that provides greater insight into the history of economic change and cultural contact.

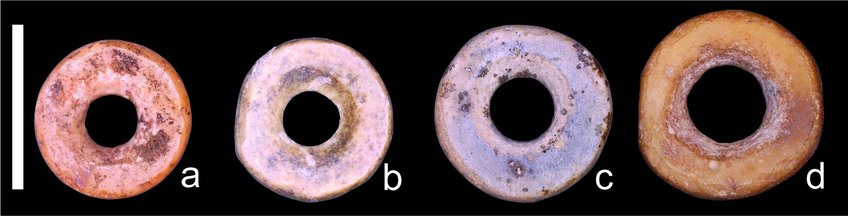

Ostrich eggshell beads are some of the oldest ornaments made by humankind, and they can be found dating back at least 50,000 years in Africa. Previous research in southern Africa has shown that the beads increase in size about 2,000 years ago, when herding populations first enter the region. In the current study, researchers Jennifer Miller and Elizabeth Sawchuk investigate this idea using increased data and evaluate the hypothesis in a new region where it has never before been tested.

Review of old ideas, analysis of old collections

To conduct their study, the researchers recorded the diameters of 1,200 ostrich eggshell beads unearthed from 30 sites in Africa dating to the last 10,000 years. Many of these bead measurements were taken from decades-old unstudied collections, and so are being reported here for the first time. This new data increases the published bead diameter measurements from less than 100 to over 1,000, and reveals new trends that oppose longstanding beliefs.

Herd of cattle grazing near Magubike Rockshelter, Tanzania.

The ostrich eggshell beads reflect different responses to the introduction of herding between eastern and southern Africa. In southern Africa, new bead styles appear alongside signs of herding, but do not replace the existing forager bead traditions. On the other hand, beads from the eastern Africa sites showed no change in style with the introduction of herding. Although eastern African bead sizes are consistently larger than those from southern Africa, the larger southern African herder beads fall within the eastern African forager size range, hinting at contact between these regions as herding spread. “These beads are symbols that were made by hunter-gatherers from both regions for more than 40,000 years,” says lead author Jennifer Miller, “so changes – or lack thereof – in these symbols tells us how these communities responded to cultural contact and economic change.”

Ostrich eggshell beads tell the story of ancient interaction

A string of modern ostrich eggshell beads from eastern Africa.

The story told by ostrich eggshell beads is more nuanced than previously believed. Contact with outside groups of herders likely introduced new bead styles along with domesticated animals, but the archaeological record suggests the incoming influence did not overwhelm existing local traditions. The existing customs were not replaced with new ones; rather they continued and incorporated some of the new elements.

In eastern Africa, studied here for the first time, there was no apparent change in bead style with the arrival of herding groups from the north. This may be because local foragers adopted herding while retaining their bead-making traditions, because migrant herders possessed similar traditions prior to contact, and/or because incoming herders adopted local styles. “In the modern world, migration, cultural contact, and economic change often create tension,” says Sawchuk, “ancient peoples experienced these situations too, and the patterns in cultural objects like ostrich eggshell beads give us a chance to study how they navigated these experiences.”

The researchers hope that this work inspires a renewed interest into ostrich eggshell beads, and recommend that future studies present individual bead diameters rather than a single average of many. Future research should also investigate questions related to manufacture, chemical identification, and the effects of taphonomic processes and wear on bead diameter. “This study shows that examining old collections can generate important findings without new excavation,” says Miller, “and we hope that future studies will take advantage of the wealth of artifacts that have been excavated but not yet studied.”