Shedding New Light on the Ancient Mediterranean

The partners of the new Max Planck-Harvard Research Center are investing a total of five million Euros in order to understand the key processes that shaped human history in the ancient Mediterranean by using cutting-edge scientific approaches.

Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena and the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, are collaborating in a new Research Center devoted to the archaeological and scientific study of the ancient Mediterranean. The Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean (MHAAM) will be inaugurated with a festive opening ceremony on Tuesday, 10 October, 2017 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. "The Max Planck-Harvard Research Center has an impressive interdisciplinary and innovative research program. The most up-to-date genetic research methods are combined with established approaches of archaeologists and historians. This closes the gap that still exists between the natural sciences and the humanities when it comes to researching great questions of human history,” says Max Planck Society President Martin Stratmann.

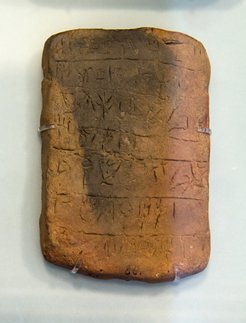

The first settlers in the Mediterranean crossed the sea to settle and connect with lively networks in various regions of northern Africa, western Asia and southern Europe. Intercultural encounters and exchanges, combined with extensive mobility of people, have characterized the development of the different cultures since then. Researchers at Harvard University and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, both leaders in this research area, are now turning their focus to these processes, which include the first "globalization" of the eastern Mediterranean area in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age (ca. 1600-1000 BC) and the so-called "Phoenician" and "Greek" migrations in the early 1st millennium BC throughout the Mediterranean.

Thanks to the genomic revolution and accelerating progress in methods to analyze DNA from ancient skeletons, it is now possible to reconstruct the genomes of ancient people. These studies lead to entirely new insights into the genetic history of all continents. “DNA and isotope analyses of human skeletal remains are an effective tool to explore human mobility and biological relatedness in the past,” says Johannes Krause, director at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, one of the directors of the new research center.

Reconstructing the past

The scientists leading the new Max Planck-Harvard Research Center highlight its interdisciplinary approach. Alongside Krause, the co-director of the research cooperation will be Michael McCormick, Goelet Professor in the Department of History at Harvard University and Chair of the Initiative for the Science of the Human Past. Philipp W. Stockhammer of LMU Munich, Institute for Pre- and Protohistoric Archaeology and Archaeology of the Roman Provinces, and David Reich of Harvard Medical School, Department of Genetics, are the deputy directors of the Center.

Alongside ancient human mobility, the project also studies the ancient spread of infectious diseases. As Krause emphasizes, the movements of bacterial pathogen and human movement were likely as closely connected in ancient times as in modern ones. Pandemics could transform entire habitats and culminate in extensive movements of populations and deep cultural change. “By bringing together isotope, DNA and pathogen analyses with deeply researched historical and archaeological evidence, the researchers will draw a dynamic new picture of the ancient past,” summarizes co-director McCormick.

Harvard University and the Max Planck Society will each invest around 2.5 million Euros in the collaborative endeavor, initially planned for a period of five years. In addition to the bilateral use of existing facilities, the effort also includes integrated transatlantic Ph.D. programs of fully funded graduate students and constant transatlantic scientific interaction and meetings via the internet and on both sites, to produce a new generation of a new kind of researcher, as well as abundant new insights into the deep historical and biological forces that produced the modern world.

17 Max Planck Centers worldwide

The Max Planck Society conducts basic research in the natural sciences, life sciences, social sciences, and the humanities at its 84 institutes. Since its establishment in 1948, 18 Nobel laureates have emerged from the ranks of its scientists. In addition to five institutes abroad, there are currently 17 Max Planck Centers worldwide. There are eight centers in Europe, including ETH Zurich, EPFL Lausanne, and University College London. The Max Planck-Harvard Research Center for the Archaeoscience of the Ancient Mediterranean is one of two Max Planck Centers in the United States.