Ostrich Eggshell Beads From the Kalahari Indicate Regional Connections, Local Innovation in Late Stone Age Southern Africa

A recent study published in the journal PLOS ONE provides technological data for a newly described Ostrich Eggshell assemblage dating to roughly 15,000 years ago, comparing this with other contemporaneous assemblages to shed light on social networks in southern Africa.

The creation, manipulation, and use of symbols for communication is key to developing and maintaining social connections within and between groups. Just as we communicate through the symbolism of jewelry today – think of a what is conveyed by a diamond ring, a leather bracelet, or a wooden ear piercing – people in the distant past created and used jewelry to embody their cultural identities and communicate about themselves within and between groups. One of the earliest forms of jewelry, ostrich eggshell beads, can help us to understand past traditions of personal ornamentation. Despite their importance ostrich eggshells have often been overlooked, but recent studies have begun to examine the beads in great detail, including in the 2021 discovery of a 50,000 social network in Africa made by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

Now a publication led by Amy Hatton, a Doctoral Researcher in the Extreme Events research group, collaborating with Dr Benjamin Collins (University of Manitoba), Dr Jayne Wilkins (Griffith University) and Dr Benjamin Schoville (University of Queensland), reports the first detailed technological study of ostrich eggshell beads in the Kalahari from Marine Isotope Stage 2 (MIS 2), a period ranging from 29-12 thousand years ago that includes the last glacial maximum. The ostrich eggshell assemblage is also contextualised by comparison with other assemblages across southern Africa that have also been dated to MIS 2.

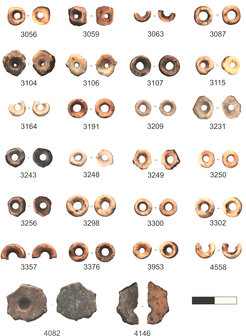

Ga-Mohana Hill North is an archaeological site in the Kalahari Basin, South Africa with occupation spanning from recent years to 105 thousand years ago. In the new study, archaeologists analysed ostrich eggshell beads and fragments from layers dating to approximately 15 thousand years ago. Their analysis shows that beads were likely manufactured at the site, due to the presence of all stages of bead production and one bead that was potentially manufactured following a less common production technique where the fragment is shaped into a rough circle before drilling the aperture.

The beginning of MIS 2 correlates roughly with a shift between technological phases termed the ‘Middle Stone Age’ and the ‘Later Stone Age’ by researchers - the latter characterized by an increasing variety of bone and stone tools. MIS 2 is hypothesised to be a period of social coalescence, supported by the similarity in tool production techniques, implement types, provisioning systems and evidence for different types of ornamentation. The presence of ostrich eggshell beads across southern Africa during this period indicates their social importance, and shows that their use was shared knowledge between populations and groups living in diverse parts of southern Africa. These findings add to other lines of evidence indicating region-wide social connections, emphasizing MIS 2 as a period of social coalescence in southern Africa.

Yet while the beads show region-wide connections, they also reveal stylistic differences in terms of bead diameter during the terminal Pleistocene. Through analysis of ostrich eggshell bead assemblages from across southern Africa during MIS 2, the authors of the new study show that while social networks were persistent during this period, there was also an increase in local stylistic innovation. In this respect, the authors suggest that ostrich eggshell beads were being manufactured at Ga-Mohana Hill North, but that the practice was not as intensive as other sites that have been described as “bead factories”.

The new paper adds to the growing number of studies reporting technological data of ostrich eggshell bead assemblages in recent years, but the beads have more insights to share. “Studying OES beads can give us insights into social interaction and how people might have used these networks to buffer environmental changes,” says lead author Amy Hatton.