Analysis of Human Teeth Demonstrates Mixture of Fishing, Foraging, and Food Production in Central Africa’s Iron Age Rainforests

The rainforests of the Congo Basin are thought to have been barriers to the expansion of agriculture during the Iron Age, with farming dependent on climate-driven or anthropogenic deforestation. In a new paper, however, a multidisciplinary team shows that domesticated millet was incorporated into an ongoing reliance on local fish and forest foods, demonstrating mixed subsistence practices in the rainforests of Central Africa for thousands of years.

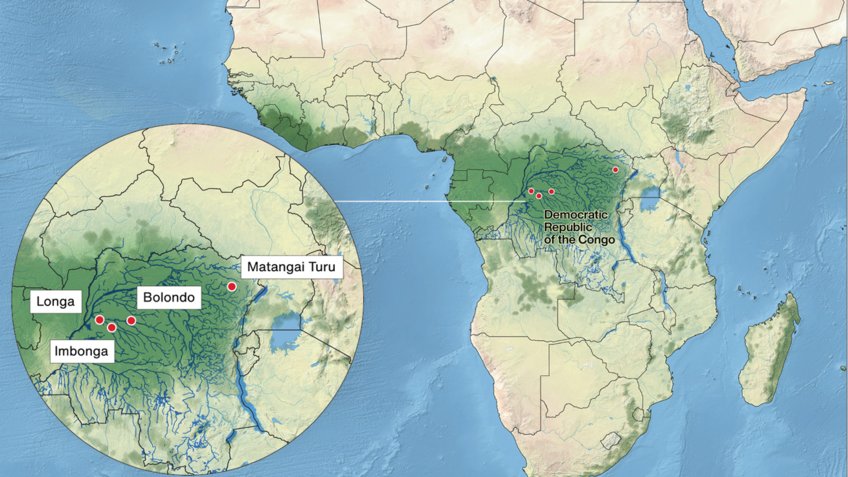

Map showing the sites of study in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The origin of agriculture across Africa has long been association with the mass migration of Bantu-speaking farmers out of western Central Africa ~4000 years ago, bringing with them iron technologies and agricultural crops, namely pearl millet. Since most domestic crops are not well-suited to tropical environments, the rainforests of Central Africa have often been viewed as barriers to these early agriculturalists, only being occupied when conditions changed or when humans took axes to trees.

In a new study published in Communications Biology, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH), the University of Cologne, Goethe University Frankfurt and the University of Calgary provide new, direct evidence of the diets of some of the first known food producers to occupy parts of the Congo Basin of Central Africa during the Iron Age.

Modern growing experiment of pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) in the Inner Congo Basin conducted by Hans-Peter Wotzka and collegues. (Wotzka 2019)

“Although we know millet arrived in the region around 2300 years ago,” says senior author Prof. Hans-Peter Wotzka from the University of Cologne, “it was difficult for us to determine exactly how it was incorporated into human diets at this time.” Although some scholars have suggested millet would grow poorly in the rainforest, Wotzka has previously undertaken growing experiments showing it can be grown successfully in the Inner Congo Basin.

In this new study, the team performed isotopic analysis of human tooth enamel and collagen extracted from human bones to see what past humans in the region were consuming. This method relies on the ‘you are what you eat’ principle, with chemical signatures in human tissues providing indications of what was eaten – in this case showing whether past communities were predominately eating local, wild resources or new, incoming cereal crops.

The results showed differences in dietary signals from different parts of the Congo Basin, with sites ranging from the western tributaries to the north-eastern edge.

“Our results reveal regional variability in the adoption of new crops across the Congo Basin,” says lead author Madeleine Bleasdale, “and add to an increasingly complex picture for the emergence of agriculture across Central Africa.”

At sites in the western tributaries, the heart of the Congo Basin, isotopic analysis indicated limited use of millet alongside an ongoing reliance on fishing and forest plants and animals. Interestingly, there may be a stronger signal of millet consumption in later life for some individuals, perhaps indicating a more restricted, symbolic use for this new crop. Indeed, millet is known to be used for brewing beer in many western African societies today.

In contrast to these more westerly sites, an individual in the Ituri Forest of the eastern Congo Basin, previously thought to have been a hunter-gatherer, had isotopic measurements strongly suggesting the significant consumption of a crop such as sorghum or millet. This was further supported by plant remains trapped in the dental plaque of this individual, which suggest the consumption of sorghum, as well as yam and oil palm.

Together, the results provide direct insights into the diets of some of the first people farming in parts of the rainforests of Central Africa.

“Unlike sweeping models of migration, deforestation and subsistence change based on genetic and linguistic approaches,” adds Bleasdale, “context-specific approaches such as this highlight how past societies fit incoming crops into unique ecological settings, making the most of what was around them and adapting food production to unique contexts.”

The rainforests of Central Africa play a crucial role in global weather systems and biodiversity. However, tropical rainforests are often viewed as barriers to cereal agriculture and the global demand for high-yielding crops has led to devastating deforestation in other regions of the world.

“Our findings confirm that mixed subsistence practices have been present in the Congo Basin for thousands of years,” adds corresponding author Dr. Patrick Roberts. “The continuation of these diverse, flexible practises are crucial to ensuring long-term food security in the region today.”